The Workforce Challenge in Clinical Labs: Tackling the Staffing Shortage (Part 1)

Part 1 of a 2 part series addressing laboratory workforce shortage

Ask any lab director what keeps them up at night, and you’ll often hear the same answer: staffing. Across the U.S., clinical laboratories are grappling with a severe shortage of medical laboratory technologists (MLTs), medical laboratory scientists (MLS), and phlebotomists.

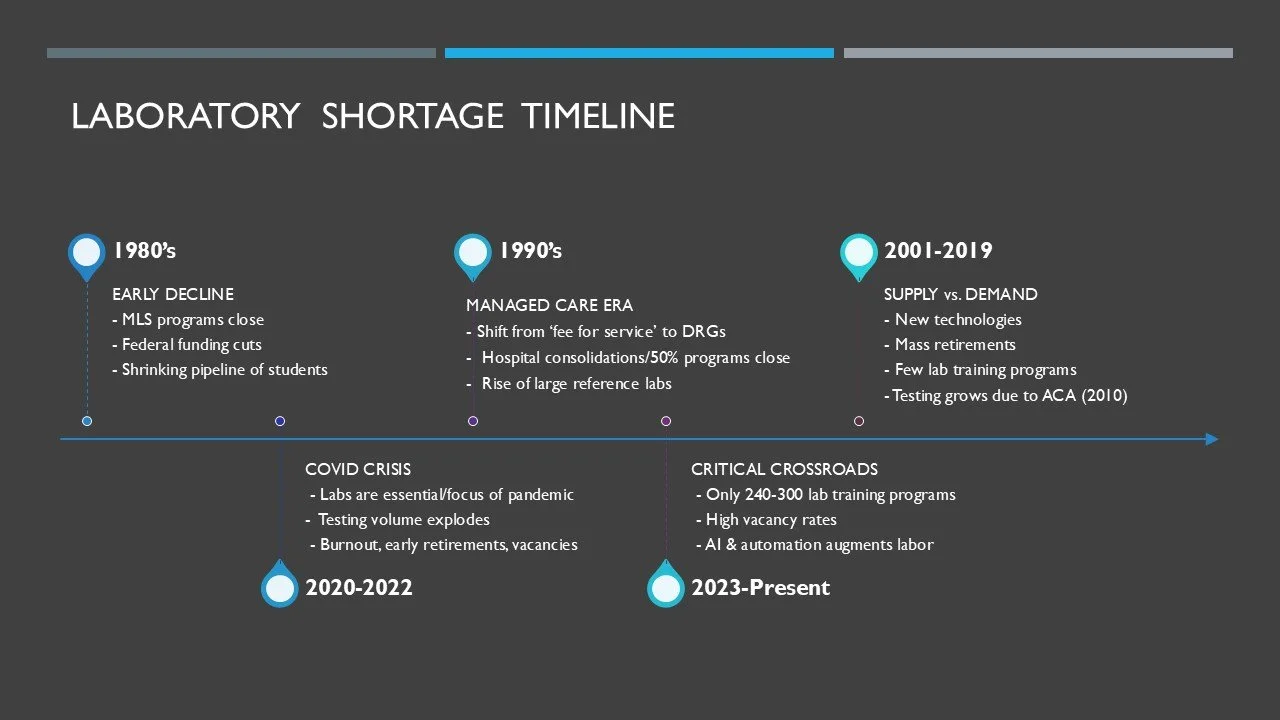

This shortage isn’t a sudden crisis—it’s the result of a slow, decades-long unraveling. But as testing volumes climb and budgets tighten, the profession finds itself at a breaking point. To understand how we got here, we need to rewind the story.

The Slow Decline of Laboratory Training Programs

The story begins in the 1980s. Back then, university-based medical technology programs were quietly disappearing. Enrollment was dropping, federal funding for allied health training was cut, and hospitals were less willing to sponsor costly clinical training programs.

At the same time, the laboratory profession remained nearly invisible to students compared with nursing, pharmacy, or medicine. Few college advisors even mentioned “medical laboratory science” as a career path. As programs closed and awareness declined, the pipeline of future laboratorians began to shrink—an early warning sign of the shortages to come.

Managed Care and the Changing Value of Lab Testing

The 1990s ushered in a decisive shift away from fee-for-service reimbursement. The use of Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs)—introduced to Medicare in the early 1980s—required hospitals to receive a fixed payment per case rather than for each individual test. This change pressured hospitals to cut costs and streamline operations, often reducing the perceived value of laboratory services. As testing became bundled into DRG payments, many institutions began consolidating in-house labs or relying on larger reference labs to capitalize on economies of scale

Instrument automation also entered the scene, promising efficiency. But while it temporarily eased pressure on staffing, it accelerated another trend: program closures. At one point, nearly half of training programs vanished (Castillo, 2000). According to NAACLS, the number of accredited MLS programs plummeted from just over 700 in 1975 to around 240 by 2000 (NAACLS, 2023).

Supply and Demand in the 2000s

The new millennium ushered in innovation—automation, middleware, and molecular diagnostics—but with it came more complexity and demand for advanced skills. Meanwhile, laboratorians trained in the 1970s and 1980s were heading into retirement.

The pipeline couldn’t keep pace. With fewer programs and limited clinical placements, many students interested in laboratory work were funneled into other healthcare professions. Then came the Affordable Care Act (2010), which expanded access to healthcare and boosted test volumes nationwide. Rural hospitals, already struggling with recruitment, faced especially steep challenges. In addition, the pay for laboratory scientists did not keep pace with other allied healthcare professions, further decreasing the interest in a lab career.

The Aftermath of COVID-19

And then came COVID-19—a cataclysm that thrust laboratories into the spotlight. For perhaps the first time in modern history, laboratorians were seen as front-line, essential workers, running tests at unprecedented volumes.

But the cost was enormous. Exhaustion, burnout, and early retirements left lasting scars on the workforce. Even today, testing volumes remain high, with molecular diagnostics becoming central to patient care. Yet there are fewer than 300 MLS programs nationwide, and vacancy rates in specialties like microbiology and blood banking remain alarmingly high (NAACLS, 2023; Leber, Peterson & Dien Bard, 2022).

Automation and AI tools are beginning to reshape workflows, but they also add new layers of complexity to workforce planning.

Root Causes of the Shortage (Since the 1980s)

For more than 40 years, the supply of clinical laboratorians has not kept pace with demand. The reasons are many:

Program Closures & Limited Training Capacity – shrinking the talent pipeline.

Low Visibility & Awareness – few students know this career exists.

Stagnant Wages – compared with nursing, pharmacy, or other health fields.

Increased Testing Demand – more tests, fewer people.

An Aging Workforce – retirements outpacing replacements.

Healthcare Cost-Cutting – consolidations, outsourcing, and overreliance on automation.

The shortage of laboratory professionals is not a new story—but it is one that has reached a critical point. In Part 2 of this series, we’ll explore where the profession is headed next: the role of AI and automation, new approaches to education and recruitment, and how labs can prepare for the future.

Reference

Castillo JB. The decline of clinical laboratory science programs in colleges and universities. J Allied Health. 2000 Spring;29(1):30-5. PMID: 10742953.

National Accrediting Agency for Clinical Laboratory Sciences. President’s Report – Educational Programs: Threats and Opportunities. St. Louis, MO: NAACLS; 2023. https://naacls.org/presidents-report-educational-programs-threats-and-opportunities/. .

Leber AL, Peterson E, Dien Bard J. The hidden crisis in the times of COVID-19: critical shortages of medical laboratory professionals in clinical microbiology. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60(8):e0024122. doi:10.1128/jcm.00241-22. The hidden crisis in the times of COVID-19: critical shortages of medical laboratory professionals in clinical microbiology. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60(8):e0024122. doi:10.1128/jcm.00241-22.